Updated: |

Beginner’s Guide To Secure VPS

The cost of a compute service varies greatly by provider and features.

As of August 2025, a server with 4 vCPUs and 8GB of RAM can cost the following:

- OVHCloud: $5.25/month

- Hetzner: $9.46/month

- DigitalOcean: $48/month

- Azure: $86.87/month

- Render: $175/month

Reference: https://getdeploying.com/reference/compute-prices

Usually, the more features/conveniences you want, the more you pay. But after a certain point, the cost difference makes you wonder: “What am I really paying for? And can I just do this myself?”.

If you just want to play around with a Linux VM locally, check out Orbstack on macOS

- Setting Up VPS

- Secure User Management

- SSH Hardening

- Firewall Configuration

- Intrustion Prevention

- Automated Security Updates

Setting Up VPS

For the purposes of this guide, we’ll be using the Hetzner platform.

Before creating a server on Hetzner, it is recommended to generate a pair of SSH keys (Hetzner disables root password authentication if we enabled SSH when creating a server). SSH authenticaiton is safer because password authentication can be brute-forced as we’ll see in a bit.

Navigate to the local ~/.ssh directory and run the following command:

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your_email@example.com"This will generate a pair of SSH keys like so:

~/.ssh/id_hetzner(private key, never share this with anyone)~/.ssh/id_hetzner.pub(public key, can be shared)

On Hetzner dashboard, find “Security > SSH Keys” and paste in the public key.

Next, we can create a server. This is the server spec I went with:

- Location: Nuremberg, Germany

- Image: Ubuntu 24.04 LTS

- Type: CX22, 2 vCPUs, 4GB RAM, 40GB SSD, €3.95/m

- Network: IPv4, IPv6

- SSH Key: the

id_hetzner.pubkey we generated earlier - Backup: it is recommended to enable regular backups for any serious purposes.

Once the server is created, we can connect to it via SSH with our key:

ssh -i ~/.ssh/id_hetzner root@<server_ip>Congratulations, you now own a server! 🎊

If we enter the following command in the server terminal:

tail -f /var/log/auth.logWe may start seeing logs like this:

Received disconnect from <ip-address> port 50952:11: Bye Bye [preauth]Disconnected from <ip-address> port 50952 [preauth]Failed password for root from <ip-address> port 59134 ssh2Invalid user ubuntu from <ip-address> port 45406These logs indicate that our VPS is already receiving automated connection attempts (To know what exactly is happening, LLM is your friend). In this post, we will address the following issues:

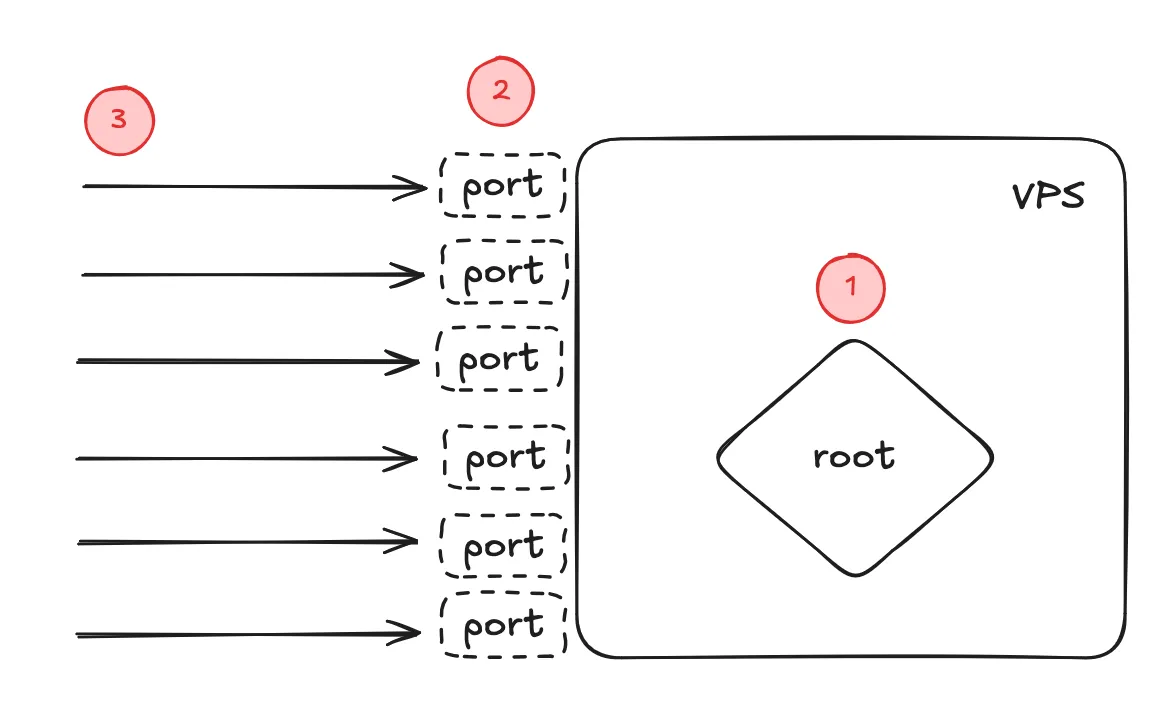

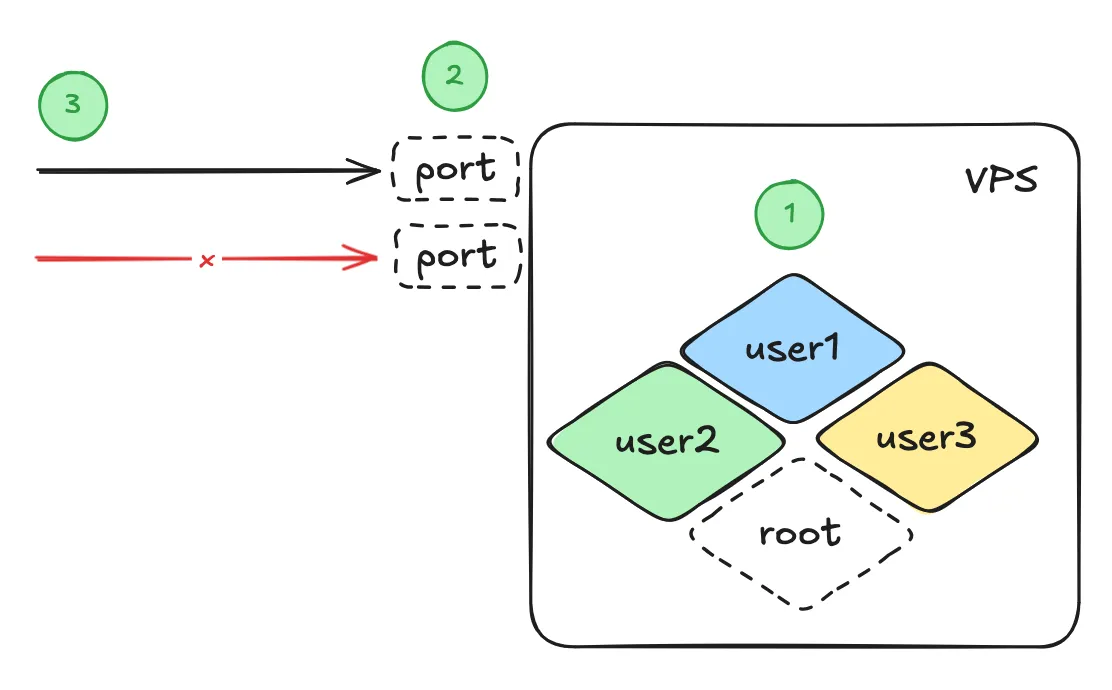

- We logged in as the

rootuser by default, which can execute privileged commands without restrictions. Hence why the bots are trying to gain access and execute commands as therootuser. We can mitigate this by disallowing therootuser from logging in and setting up a non-root user withsudoprivileges (the user still be asked for password when executing privileged commands). - Currently, we have too many open ports on the VPS. The more unnecessary ports that are open, the bigger our “attack surface” is, increasing the likelihood of compromise. We can mitigate this by closing all ports that are not required for the services that we are running on our VPS.

- A high volume of connection attempts can consume our server’s resources. While typically not a full Denial of Service (DoS) by themselves, they could potentially consume resources and slow down operations on our server. We can mitigate this by blocking repeating offenders.

Our unsecure VPS with issues highlighted

Secure User Management

To solve issue 1, let’s create a new user (why not name it goku) and set up sudo privileges.

# create a new usersudo adduser goku # will be prompted for a password and basic info

# give the new user sudo privilegessudo usermod -aG sudo goku

# check the new user's groupsgroups goku # should see the `sudo` group

# switch to the new usersu - goku

# confirm current pathpwd # /home/gokuNext, the new user goku needs to know our SSH public key, so when we connect again from local machine, it can use the

server stored public key to confirm our identity and authenticate.

In the terminal, open another tab and make sure we are on the local machine:

ssh-copy-id -i ~/.ssh/id_hetzner.pub goku@<ip-address>This will copy our local SSH public key to server /home/goku/.ssh/authorized_keys. (If the ssh-copy-id command failed, the other way would be create the file /home/goku/.ssh/authorized_keys manually, and copy the content from root /.ssh/authorized_keys over)

For better security, we can generate new SSH key pairs just for the

gokuuser:

- generate key pair:

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C goku@example.com- copy it to server with the above

ssh-copy-idcommand- connect SSH with the new key:

ssh -i ./ssh/goku goku@<ip-address>The main benefit of this is that if the

gokuSSH key pair gets compromised, the hacker will only have access to thegoku@<ip-address>but not to any other servers.

Server users and groups management is a big topic, you should look into this at your own time (for example, it is often

recommended to create different users with different permissions for different tasks, e.g., a user deploy just for

deploying apps with limited permissions).

SSH Hardening

To disable root from logging in, we can edit the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file with vim:

# vim is installed by default with Ubuntu 24.04vim /etc/ssh/sshd_configFind the following configurations and change their values to:

# Disable `root` user SSH loginPermitRootLogin no

# Disable password authenticationPasswordAuthentication no

# Allow user to authenticate using public keyPubkeyAuthentication yes/etc/ssh/sshd_config is an important file and it is worth to explore other configuration options further. For example,

we can configure the server to send a keepalive message after 300 seconds (5 minutes) of inactivity, and if that single

keepalive goes unanswered, the client connection will be immediately terminated.

ClientAliveInterval 300ClientAliveCountMax 1Another popular configuration is to change the default SSH port from

22to another number, but some suggest this is not necessary. We won’t do it in this guide. But if you decide to, change thePORTvalue in thesshd_configfile from 22 to another number (a safe range is between 49152 and 65535), and make sure to reflect the new port number everywhere else (e.g., when connecting, or in firewall rules).

After making changes to the sshd_config file, we can validate the file with sshd -t (valid if no terminal output)

and restart the SSH service:

# check ssh statussudo systemctl status ssh

# restart ssh servicesudo systemctl restart ssh.serviceNow exit the server and time to test different authentication methods to our server:

- should fail to login as root

ssh root@<ip-address> - should fail to login as

gokuwithout providing valid ssh key - should fail to login as root with private key:

ssh -i ~/.ssh/id_hetzner root@<ip-address> - should only succeed when:

ssh -i ~/.ssh/id_hetzner goku@<ip-address>

Firewall Configuration

Moving on to issue 2. We can use ufw (Uncomplicated Firewall) to manage the server ports:

# check UFW status: should be "Status: inactive" for nowsudo ufw status verbose

# list available profilessudo ufw app list

# >>> IMPORTANT!!! allow SSH FIRST to prevent locking self out! <<<sudo ufw allow OpenSSH # or "allow 20"

# allow HTTP and HTTPS if you plan to host a websitesudo ufw allow http # or "allow 80"sudo ufw allow https # or "allow 443"

# Explicitly setting UFW default policiessudo ufw default deny incomingsudo ufw default allow outgoing

# Review the rules before enablingsudo ufw show addedsudo ufw enablesudo ufw status verboseTo remove any UFW rules, we can first list them by sudo ufw status numbered and sudo ufw delete <rule-number> to

remove them.

See https://documentation.ubuntu.com/server/how-to/security/firewalls for more details.

Intrustion Prevention

Lastly with issue 3, we can:

- either filter public traffic with fail2ban or crowdsec

- or, only allowed private/trusted users to access our VPS with Tailscale

It is not necessary to do both, so you can choose option 1 or 2 depending on your needs.

Option 1: Filter public access with Crowdsec

The popular fail2ban is a local solution with each server monitoring their own logs, banning repeat offenders, while crowdsec is a distributed solution that leverages a global network of servers to share and act on threat intelligence.

Here, we will use crowdsec but you can find plenty resources online about fail2ban, for example:

https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-protect-ssh-with-fail2ban-on-ubuntu-20-04

Here are the commands to install and configure crowdsec:

curl -s https://install.crowdsec.net | sudo shapt list crowdsecsudo apt install crowdsec -ysudo apt install crowdsec-firewall-bouncer-iptables -ysudo systemctl status crowdsecCheck the crowdsec log to see if it’s working properly by running:

sudo tail -f /var/log/crowdsec.log# list banned IPssudo cscli decisions listSee the CrowdSec documentation for more configuration options: https://doc.crowdsec.net. E.g., By default, CrowdSec bans any suspicious IP for 4 hours, but we can change it here: https://docs.crowdsec.net/u/getting_started/post_installation/profiles/#scaling-decision-duration

There is also a web-based interface called CrowdSec Console where we can visualise the engines’ activities.

If you make any changes to the crowdsec configuration, you can validate it and restart the service:

sudo crowdsec -t && sudo systemctl restart crowdsecOption 2: Private/Zero Trust Network with Tailscale

First, install Tailscale on the VPS with curl -fsSL https://tailscale.com/install.sh | sh, and then run sudo tailscale up --ssh.

The

--sshflag is optional, but it allows us to SSH into the VPS using Tailscale.

After authenticating the VPS on the Tailscale website, we can see a private address starting with 100.xx.xx.xx being assigned to the machine.

# we can also run this on the VPS to see the private addresssudo tailscale ip -4For example: 100.xx.xx.xx. This IP is only accessible from the Tailscale network (or often referred to as tailnet).

On our local machine, install the Tailscale app (available almost on every platform): https://tailscale.com/download and log in. Then, test the VPS connection again:

# From our local machine, not the server!# for example: ssh goku@100.x.y.zssh <user>@<tailnet_ip_address>DO NOT PROCEED until this SSH connection works. Otherwise, you may lock yourself out of the VPS. If the ssh command worked through Tailscale, then we can move onto the next step: close the public access.

This is where we block public access and only allow access from the tailnet. We will do this by telling UFW to only allow traffic from the tailscale0 network interface.

Add the new “allow” rules for Tailscale:

# Allow SSH, but only from the tailscale0 interfacesudo ufw allow in on tailscale0 to any port 22 proto tcp comment 'Allow SSH via Tailscale'

# Allow HTTP, but only from the tailscale0 interfacesudo ufw allow in on tailscale0 to any port 80 proto tcp comment 'Allow HTTP via Tailscale'

# Allow HTTPS, but only from the tailscale0 interfacesudo ufw allow in on tailscale0 to any port 443 proto tcp comment 'Allow HTTPS via Tailscale'Delete the old “anywhere” rules:

# Remove IPv4 rulessudo ufw delete allow OpenSSHsudo ufw delete allow 80/tcpsudo ufw delete allow 443

# Remove IPv6 rulessudo ufw delete allow '22/tcp (v6)'sudo ufw delete allow '80/tcp (v6)'sudo ufw delete allow '443 (v6)'We can also run

sudo ufw status numberedfirst, thensudo ufw delete [rule-number]to remove the old rules

Check Firewall status: sudo ufw status verbose, it should be something like this:

Status: activeLogging: on (low)Default: deny (incoming), allow (outgoing), disabled (routed)New profiles: skip

To Action From-- ------ ----22/tcp on tailscale0 ALLOW IN Anywhere # Allow SSH via Tailscale80/tcp on tailscale0 ALLOW IN Anywhere # Allow HTTP via Tailscale443/tcp on tailscale0 ALLOW IN Anywhere # Allow HTTPS via Tailscale22/tcp (v6) on tailscale0 ALLOW IN Anywhere (v6) # Allow SSH via Tailscale80/tcp (v6) on tailscale0 ALLOW IN Anywhere (v6) # Allow HTTP via Tailscale443/tcp (v6) on tailscale0 ALLOW IN Anywhere (v6) # Allow HTTPS via TailscaleNow, if we turn off the Tailscale app locally, and tried to connect to the VPS: ssh -i ~/.ssh/id_hetzner <user>@<PUBLIC_IP_ADDRESS>, the connection should hang and eventually timeout.

But if we turn on the Tailscale app, and try to connect again: ssh <user>@100.xx.xx.xx, we should be able to connect to the VPS as normal, through the Tailscale private network.

The True Zero Trust

We’ve barely scratched the surface with Tailscale here. Tailscale offers many more advanced features. For example, grant different permissions to users on the same Tailscale network by emails, or controlling which devices can talk to each other etc.

Refer to the Tailscale docs (https://tailscale.com/kb) for more guides and next steps.

Automated Security Updates

Our server consists of many software packages, and some of them may have security vulnerabilities that later will be

patched by CVE updates. The package unattended-upgrades allows our system to download and install security updates

automatically in the background. As of Ubuntu 24.04, the package is installed and running by default. We can confirm

this with:

cat /etc/apt/apt.conf.d/20auto-upgradesAnd we should see the following output:

APT::Periodic::Update-Package-Lists "1";APT::Periodic::Unattended-Upgrade "1";If not, consult https://documentation.ubuntu.com/server/how-to/software/automatic-updates/ for guide on how to configure

unattended-upgrades for automatic updates.

Congratulations, we’ve successfully made our VPS more secure than its initial state.

But like any other security tasks, they are never done.

There are plenty more things we can do, for example:

- Setup automatic backup system (never lose any important data)

- Setup robust monitoring and alerting system (always be notified when something goes wrong)

- Setup forwarding to use the VPS as a proxy for other services (e.g., for a VPN)

- Etc…

Maybe they’ll be the topics of my future posts, let me know if you’re interested.